The study shows that Torrejonia, a small mammal from an extinct group of primates called plesiadapiforms, had skeletal features adapted to living in trees, such as flexible joints for climbing and clinging to branches. Previously, researchers had proposed that plesiadapiforms in Palaechthonidae, the family to which Torrejonia belongs, were terrestrial based on details from cranial and dental fossils consistent with animals that nose about on the ground for insects.

The skeleton was discovered in the San Juan Basin by Thomas Williamson, Curator of Paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History&Science, and his twin sons, Taylor and Ryan, on land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) under permit.

The study in Royal Society Open Science, supports the hypothesis that plesiadapiforms, which first appear in the fossil record shortly after the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, were the earliest primates. The researchers also contend that the new data provide additional evidence that all of the geologically oldest primates known from skeletal remains, encompassing several species, were arboreal.

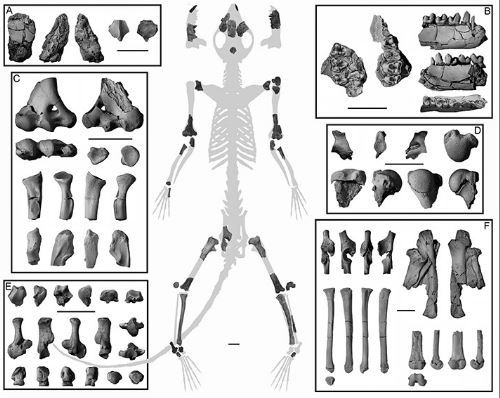

The partial skeleton consists of over 20 separate bones, including parts of the cranium, jaws, teeth, and portions of the upper and lower limbs. The presence of associated teeth allowed Williamson, a co-author of the study, to identify the specimen as Torrejonia because the taxonomy of extinct mammals is based mostly on dental traits, said Eric Sargis, Professor of Anthropology at Yale University, and a co-author of the study. “To find a skeleton like this, even though it appears a little scrappy, is an exciting discovery that brings a lot of new data to bear on the study of the origin and early evolution of primates,” said Sargis, a Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and Vertebrate Zoology at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, where the partial skeleton was molded and casted for further study.

Palaechthonids, and other plesiadapiforms, had outward-facing eyes and relied on smell more than living primates do today — details suggesting that plesiadapiforms are transitional between other mammals and modern primates, Sargis said.

Comments