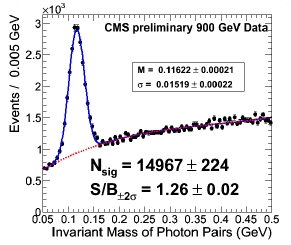

The amount of results that the collaborations have managed to produce in such a small time frame, and from a relatively small amount of collisions, is really astonishing. Of course most of them have no real scientific value, if as a yardstick you use the advancement of our knowledge of particle physics. Yet everybody was eager to know how well the performance of the detectors matches the expectations from computer simulations, and the answer is that all experiments are performing impressively, and that almost everything is understood to a level of detail I myself would have thought improbable to achieve in such a short time frame, just a few weeks ago. But then the first data came, and I saw with my own eyes the quality of the thing we have put together. As a simple starter, have a look at the CMS signal of neutral pions in their decay to photon pairs (a final state of interest for low-mass Higgs boson searches, although at an energy three orders of magnitude larger!). The black points in the histogram below are 900 GeV data, the blue line is the fit including the signal, and the red dashes show the background fit.

I was especially pleased to see that the effort of the small group of physicists from Padova and Cyprus which my colleague Franco and I have managed to put together has not been vain. We have been working day and night in the last two weeks, in order to produce an approved signal of the

Some background on the Phi meson

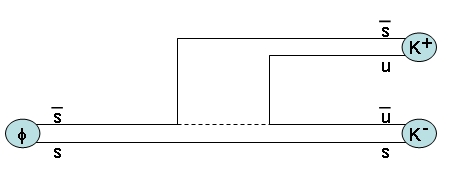

To explain those reasons, I need to give you some background. We reconstruct phi meson decays in two charged kaons, as in

Strong interactions are incapable of turning a quark into one of a different species, so the two strange quarks manage to survive inside the kaon daughters. You see that in the sketch on the right (read it from the left to the right, as if time went rightward): strong interactions "fish" a up-antiup-quark pair from the vacuum, and you get two light strange mesons at the price of a heavy hidden-strangeness one. The dashed line is a gluon, which transmits colour charge and momentum to the final state, mediating the decay.

Strong interactions are incapable of turning a quark into one of a different species, so the two strange quarks manage to survive inside the kaon daughters. You see that in the sketch on the right (read it from the left to the right, as if time went rightward): strong interactions "fish" a up-antiup-quark pair from the vacuum, and you get two light strange mesons at the price of a heavy hidden-strangeness one. The dashed line is a gluon, which transmits colour charge and momentum to the final state, mediating the decay.Now, the mass of the

As for the charged kaons, they live long enough to often cross the entire tracking volume of CMS. They get reconstructed as nice helices in the solenoidal magnetic field, thanks to the small energy they deposit in each of the 13 layers of 300-micron-thick silicon detectors they traverse. Now, it turns out that the energy measured by the silicon layers is a distinguishing feature, which can tell apart different charged particles. You can see it in the figure on the left, which shows how different particles have a different behaviour of deposited energy (on the y axis) which is a unique function of the particle's momentum (the quantity shown on the horizontal axis). The figure is from ALICE (which does not use silicon for this measurement, but the physics is the same), and it is one of the results shown today. I decided to show the ALICE result because in this case it is much better than the CMS or ATLAS plots! ALICE has been designed to excel in the particle identification using the energy release of charged particles, because of its need to study very high-multiplicity events caused by heavy ion collisions.

As for the charged kaons, they live long enough to often cross the entire tracking volume of CMS. They get reconstructed as nice helices in the solenoidal magnetic field, thanks to the small energy they deposit in each of the 13 layers of 300-micron-thick silicon detectors they traverse. Now, it turns out that the energy measured by the silicon layers is a distinguishing feature, which can tell apart different charged particles. You can see it in the figure on the left, which shows how different particles have a different behaviour of deposited energy (on the y axis) which is a unique function of the particle's momentum (the quantity shown on the horizontal axis). The figure is from ALICE (which does not use silicon for this measurement, but the physics is the same), and it is one of the results shown today. I decided to show the ALICE result because in this case it is much better than the CMS or ATLAS plots! ALICE has been designed to excel in the particle identification using the energy release of charged particles, because of its need to study very high-multiplicity events caused by heavy ion collisions.Reasons why we need to study the phi resonance

So let us take stock. Here are a few reasons to study the

1- The

2- The

3- A pure sample of kaons -which we can select as the two "legs" of the

4- The

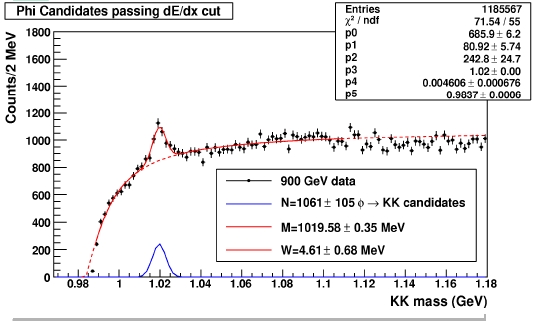

The phi signal in early data

Now, I will not spend much time describing the frantic days that have populated the last two weeks of my life. Suffices to say that I have worked about 50% more than what I usually do, or twice as much as I would like to, or three times as much as what I am paid for. A summary of the last week at CERN already exists in this column -I have described it without making reference to the signal I was searching for, because it was not approved material yet.

The Ph.D. student I am co-advising, Luca, can complain further in the comments section if he likes; the same can be said of the undergraduate who also works with us, Pierluigi, and of the post-doc from Cyprus University, Mario. All these folks have lost significant amounts of sleep to put together the single figure I am posting today. Science is tough!

The histogram below shows the mass distribution of opposite-charge pairs of particles reconstructed in the CMS silicon tracker. The tracks have been selected by enforcing the characteristics we expect for kaons produced in

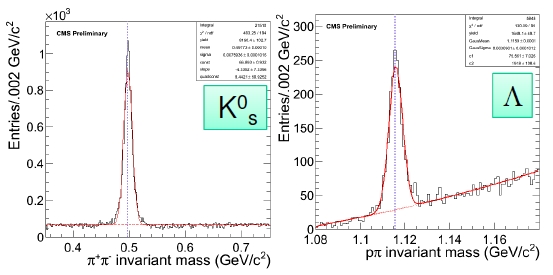

In the next weeks we will use the data collected by CMS so far (about 400 thousand good events at 900 GeV, plus a few tens of thousands at 2.36 TeV) for a preliminary estimate of the probability of kaons, pions, and protons yielding muon tracks, using the

LHC is finally on, and we mean business!

Comments