Global warming is melting ice in the Arctic and that means more cold water entering the oceans. How it will affect ocean currents is unknown, numerical models of chaos being pretty useless, but there is a way to at least start to find out - throw a biodegradable bottle off a ship and wait for it to wash ashore. If it turns up some place you never expected or lands where you expect but much faster than models show, it could be evidence of ocean current change and, with that, changes in weather.

Enter Bonita LeBlanc, an 11th grader from Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, and her drift bottle experiment. How did she get this cool research project at an age when I was ... well, we won't get into that ... but here's how; when she was 13, LeBlanc read an article about Eddy Carmack, a Canadian oceanographer conducting drift bottle research off the coast of Brazil.

So she got in touch with with him and asked how she could start doing drift bottle research too. Eddy told her to contact the Canadian Coast Guard, which agreed(!) to drop bottles for her from the icebreaker CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent - shameless plug for companies doing a nice thing: the 100 percent biodegradable bottles were donated by Sleeman Breweries - double bonus, the Sleeman family were booze runners during Prohibition (the Canadian version first) so he knew how to use a Thompson.

So LeBlance wrote notes saying why the bottles were being dropped and who to contact if they were found, corking and coating each one with wax to make a waterproof seal.

Science!

Looks like a lot of work, right? Obviously science is not always "Splice"-ish creating-new-life-that-tries-to-kill-you, as fun as that sounds. It is often tedious, the kind of thing you assumed you would never have to do thanks to a college degree.

No matter how hysterical corporate media gets about Venter's synthetic genome, your career is statistically unlikely to be this much fun.

For two years, the CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent’s crew tossed nearly 600 of LeBlanc's bottles into the Arctic Ocean but finally in 2009, during the International Polar Year, Youth Science Canada program selected a lucky student (LeBlanc) to join the crew of the research ship CCGS Amundsen and she got the chance to throw them overboard herself.

What was that like? Being seasick and shivering through -40º C temperatures can't be all that great but she got to hang out with oceanographers and talk about their work - and eat some caribou.

Don't tell Greenpeace about that last part.

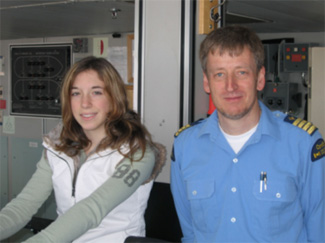

Commanding Officer Anthony Potts, CCGS Louis St.Laurent, and Bonita LeBlanc at the beginning of her drift bottle project in 2006. Photo: Natalie Cordiner / Norman LeBlanc

So what was the result?

Only four percent of all drift bottles are ever found - most sink, get buried in sand or wash up in a spot where people never find them. Of the hundreds of bottles from LeBlanc’s first batch, seven have been found—three on Baffin Island, two in Ireland, one in England and one in Iceland. It normally takes a few years for a bottle to make its way to shore so her most recent bottles are still floating somewhere in the ocean.

Comments