A preamble

Subnuclear physics obeys the laws of quantum mechanics, which are quite a far cry from those of classical mechanics we are accustomed to. For that reason, one might be inclined to believe that analogies based on everyday life cannot come close to explaining the behavior of elementary particles. But that is not true – in fact, many properties of elementary particles are understandable in analogy with the behavior of classical systems, without the need to delve into the intricacies of the quantum world. And if you have been reading this blog for a while, you know what I think – the analogy is a powerful didactical instrument, and it is indeed at the very core of our learning processes.

The above has a relevance here because in this post I wish to try and explain in as simple terms as possible how subnuclear particles decay. I took inspiration for this from a recent conversation I had with my son, who was asking explanations on a non-trivial rule that forbids some quantum mechanical decay processes. The rule, called OZI (from the names of the three theorists who proposed it in the 1970ies, Okubo, Zweig, and Iizuka), applies to hadrons (particles made of quarks) disintegrating into other hadrons. I will get to it later in this article, but first I want to clarify a few more fundamental concepts about particle decays.

Particle decay is the transformation of a “parent” particle (I will also refer to it as the “initial state” of the reaction) into “daughters” –other particles globally referable to as “final state”). This reaction is fueled by the larger mass of the parent with respect to the sum of the masses of all daughters: as mass is energy, then there is enough energy for it to take place. Here we are exploiting Albert Einstein’s famous “E = Mc^2” formula: the mass of a particle can transform into the energy and mass of others. That formula alone also explains why some particles do not decay at all (although not all particles live forever only because of that): their immortality is guaranteed by energy conservation, as there are no lighter particles into which they may turn. But why does that happen, anyway? Why do particles decay instead of holding on to their mass forever?

The reason is a very general fact that applies to galaxies, planets, hippopotamuses, mosquitoes, molecules, all the way down to elementary particles: everything that is not forbidden by a law of physics, does happen. Since energy conservation is an unbreakable law of physics (at least as far as we know today), a particle of mass M cannot turn into a system of other particles whose total energy is collectively larger than E=Mc^2. In fact, all reactions that do happen satisfy the equivalence of those two quantities. So, suppose a particle of mass 1 (in whatever units) wants to decay into two particles of mass 0.3: this is possible, as the sum of the two daughters mass is 0.6. The leftover in the energy budget, 0.4, will be shared by the two daughters in the form of kinetic energy. While the details of this legacy division require knowledge of special relativity to be worked out, the general rule is quite simple: the parent can decay into daughters whose total mass does not exceed its own. And it will do so, as long as there are no other laws that take exception.

Let us pause for a second and try to reckon with the above situation. In classical systems the very same thing indeed applies: if you let a ball loose on a non-flat surface, and if friction is not large, the ball will start rolling toward lower ground. It will do so because it can: the ball must obey the laws of energy conservation, so it cannot roll uphill (it would unduly gain total potential energy, creating energy from nothing); but it can roll downhill (turning a part of its potential energy into its own motion, kinetic energy), so it will. All objects that have a chance to lower their potential energy – by rolling downhill, or by falling down – in fact do so. This basic fact is at the basis of every law of motion, from chemical reactions to planetary systems and up.

Composite systems

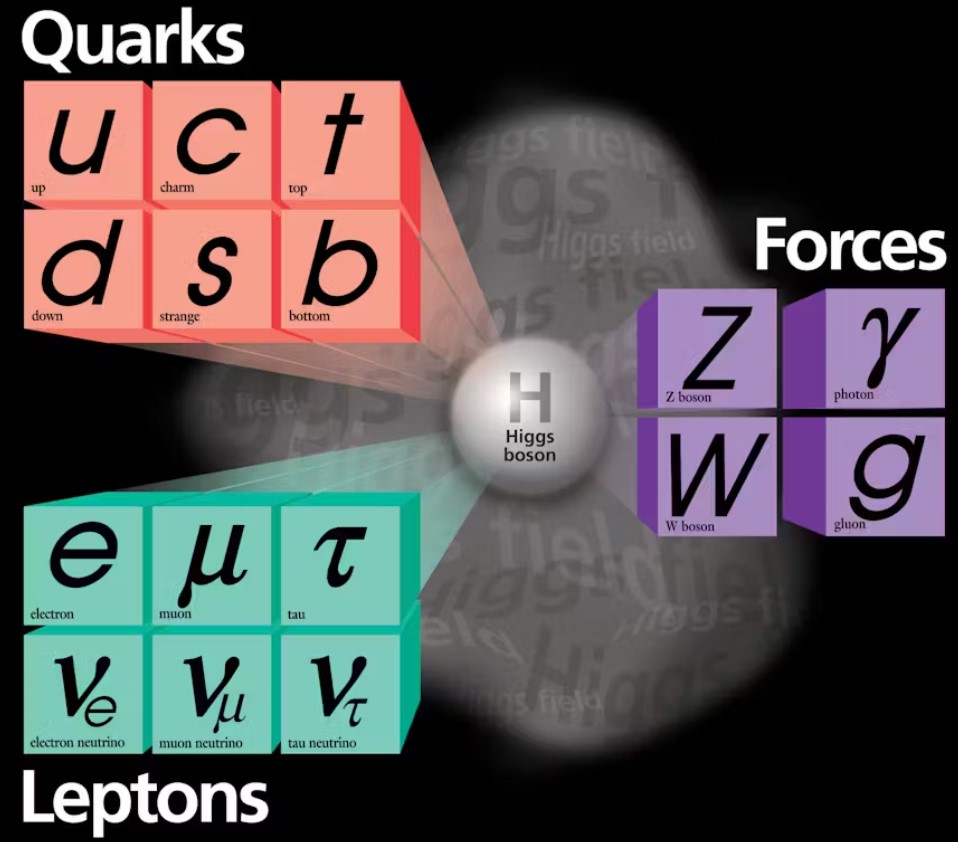

Subnuclear particles making up matter are either truly elementary, or they are built as a combination of some elementary blocks. We call the latter quarks and leptons. Quarks make up protons and neutrons, the ingredients of atomic nuclei; and leptons include the electron plus heavier replicas of the latter, as well as three ephemeral, lightweight bodies called neutrinos. And then there are subnuclear particles that transmit forces of nature. These include the photon (which carries electromagnetic interactions), the gluon (the glue that carries strong interactions binding quarks inside protons and neutrons), the W and Z bosons (carriers of a third force called “weak interaction”), the Higgs boson (a magical particle permeating space and with which all massive particles interact, thereby “slowing down” and acquiring an inertial mass) and gravitons carrying the gravitational interactions. We will ignore the latter in the following, as it does not belong to subnuclear particle phenomenology (gravity is too weak compared to all other forces to make any difference in the proceedings). The picture below shows the elementary particles, both matter ones (quarks and leptons) and force carriers.

It takes three quarks to form the proton (two up-type quarks and one down-type quark); and it similarly takes three quarks to form the neutron (two down-quark and one up-quark). Due to the slightly higher mass of the down quark, the neutron weighs a bit more than the proton. This makes the neutron unstable, as its mass (which is akin to potential energy, in a sense) can turn into mass and energy of a proton plus an electron-antineutrino pair. The process is called “beta decay” and it is a very, very slow one for subnuclear world standards (the neutron lifetime is of 15 minutes!), as although energy conservation allows it, there is a practical difficulty in subdividing the total energy of the decaying neutron into mass of the proton, electron, antineutrino, plus kinetic energy of the three daughters. It is a bit as if the neutron had to wait for a long time before the three daughters could negotiate the splitting of the energy legacy (the mass of the parent), when this was made difficult by each of them getting some real estate (their mass), but none of them getting enough cash (kinetic energy to run away with) in addition.

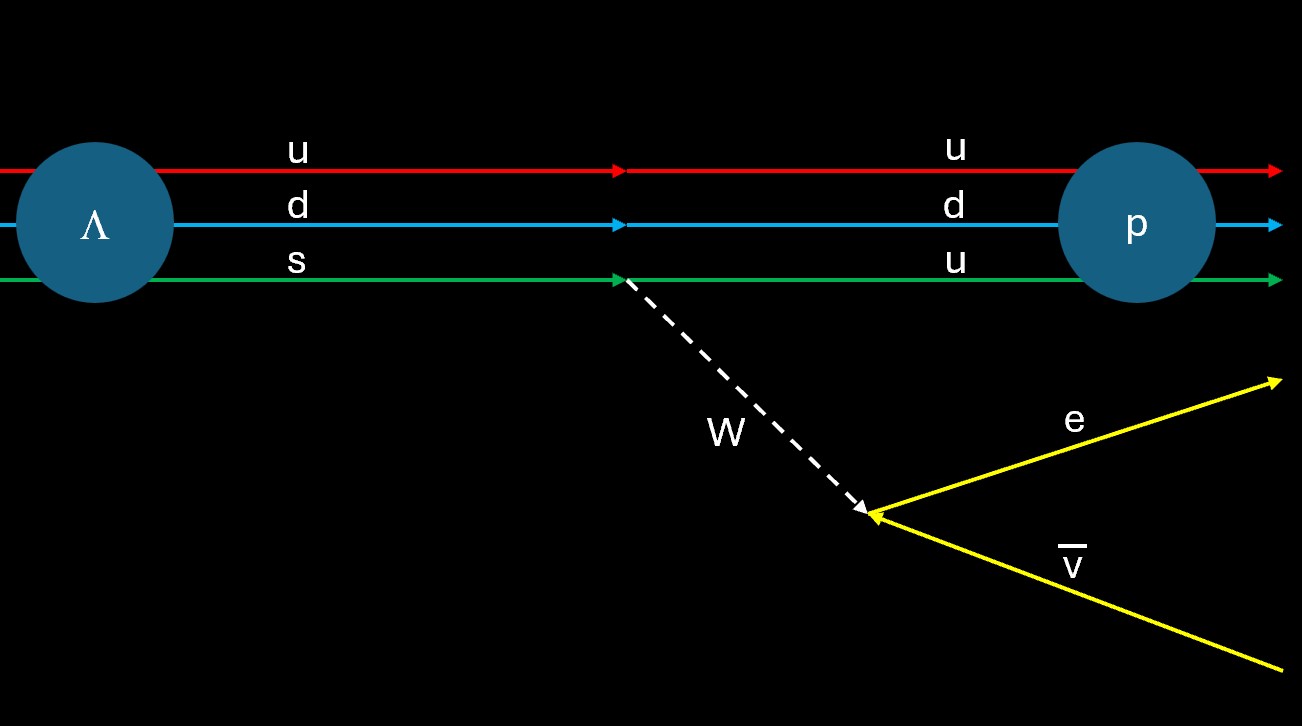

The neutron decay is a case when the “phase space” for its only possible disintegration mode is very small. Phase space is a space whose dimensions are the kinetic energies of each decay product. A small phase space (very little energy to share) makes the decay very slow. Compare the neutron situation to that of the Lambda particle, which is similar in composition to the neutron: it is made of an up, a down, and a strange quark, so you get it by exchanging one of the neutron’s down quarks for a strange quark. The strange quark weighs more than the down quark, so while the neutron weighs 939 MeV, the Lambda weighs 1116 MeV. This allows the latter to decay into a proton and an electron-neutrino pair much faster than the neutron.

In the graph time flows from left to right, and the vertical dimension symbolizes spatial distances. The Lambda can then be pictured as a stream of three quarks (u,d,s) moving together toward the right. The weak force may turn the strange quark into an up quark through the emission of a W boson (the weak force carrier), shown with a dashed line. The latter may then produce the electron-antineutrino pair in perfect analogy with what happens in neutron decay; but the higher mass of the Lambda makes the phase space larger: the legacy splitting is then blitzing fast, and the three resulting final state bodies (proton, electron, antineutrino) fly away in two tenths of a billionth of a second.

What a difference some added energy makes! Enrico Fermi worked out in the 1940s that, other things being equal, the rate of a beta decay grows roughly as the fifth power of the available energy (the so-called Q-value of the reaction). For the neutron, that’s only about 939.565−938.272−0.511 ≈ 0.78 MeV. But for the Lambda, the corresponding decay energy is 1115.683−938.272−0.511 ≈ 177 MeV. The ratio is about 226, and raising that to the fifth power gives nearly 6×10^11 — very close to the trillion-fold difference in lifetimes between the neutron (880 seconds) and the lambda (2.6 × 10⁻¹⁰ seconds). Subnuclear physics really does follow some elegant rules…

The Phi meson and the OZI rule

Now let me introduce the Phi meson to you. Like the proton, the neutron, the pion, and the Lambda, it is not an elementary particle but a composite one. It is composed of a strange–antistrange quark pair, and its mass is about 1019.5 MeV. This makes it possible for it to decay in a few different final states. What do the rules of the subnuclear world say about the different decays and their relative importance? Let us find out.

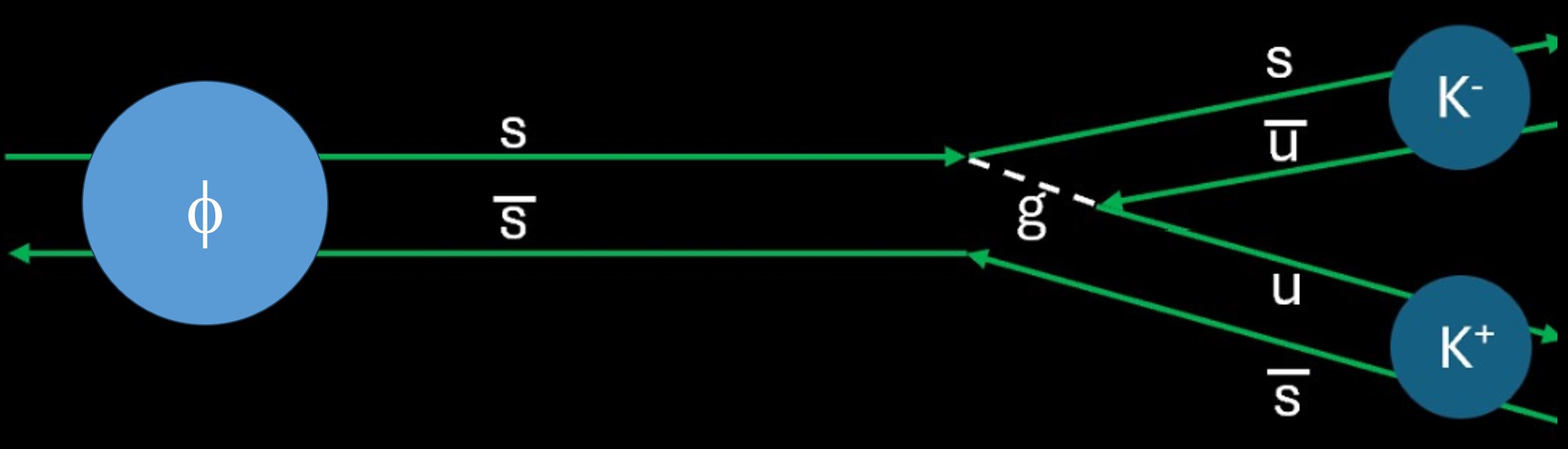

First of all, we can consider the decay of the Phi into two K mesons. This is a quite natural decay mode of the Phi, because K mesons are made of a strange or antistrange quark bound to another lighter quark (up or down, or their antiparticles, in all cases such that we get a quark–antiquark pair – quark–quark or antiquark–antiquark combinations are impossible because of another rule of the quantum world). So it is easy to picture a ϕ→K+K− decay, as shown below.

In the picture, the Phi moves toward the right until it emits a gluon (the carrier of the strong force) that immediately materializes an up–antiup quark pair. The resulting final state, after the recombination of the two quark–antiquark pairs has taken place, includes a K+ and a K−. But how quickly does that reaction proceed? Not much: kaons weigh about 494 MeV each, so the phase space for the decay amounts to only

1019.5 − 493.7 − 493.7 ≈ 32 MeV

of free energy. It is small, so the reaction proceeds rather slowly, as we learned above.

However, so far we have not considered that the emission of a gluon as in the above diagram is much, much more frequent than the emission of a W boson (which was the mediator in neutron and Lambda decay we considered earlier). Indeed, there is a reason why the two interactions are called strong and weak, respectively: a stronger interaction is something that happens more frequently (much like drops in strong rain hit you more frequently than in weak rain). If we were in subnuclear physics class we could take the various factors determining the speed of the reaction into account, but here it suffices to say that the reaction proceeds rather slowly with respect to other strong-interaction decays.

But the Phi can decay in other ways, too. For example, it can produce a ρ and a pion. The ρ meson, another quark–antiquark particle, weighs about 775 MeV, and the charged pion about 139 MeV. The two daughters together weigh 914 MeV, leaving

1019.5−775−139 ≈ 106 MeV

for kinetic energy. That’s already more than three times larger than the kaon-pair case, so the available momentum is much greater. By Fermi’s golden rule, the decay width scales roughly as the fifth power of the available energy. So the phase-space ratio is about

106/32 ≈ 3.3 ⇒ (3.3)^5 ≈ 400,

suggesting that, other things being equal, the ϕ→ρπ decay should proceed about 400 times faster than ϕ→K+K−.

Here, however, the OZI rule comes in. Since the ρ and the pion contain no strange quarks, the initial strange-antistrange quark pair of the Phi must annihilate, leaving only gluons, which then materialize light up-antiup and down-antidown pairs to form the final state. The OZI rule says that such disconnected decays must proceed through the emission of not one, not two, but at least three gluons. Leaving aside the deep reason for this, we can just say that what we are asking of the reaction is a concert of rare events: each gluon emission has a certain probability, which while not small it is strictly less than 1.0: so, requiring three at once makes the process very unlikely. The reaction, if it could proceed via a single gluon, would indeed be rapid, as the phase space allows. But having to involve three gluons strongly suppresses the rate, by roughly the cube of the strong-coupling suppression factor. That’s why, despite the ample energy available, the ϕ→ρπ (and related three-pion final states) occurs only at the percent level, while the kaon–antikaon modes end up dominating.

But how?

I was going to stop my article here, content with my explanation, and then I realized I was skipping the most interesting, most fundamental part of the issue! How to relate the Phi->KK decay to the Phiàrho pi decay in terms of relative probabilities? This is a very relevant question for an experimentalist, as she will be able to measure these relative probabilities by just counting how many decays of each kind take place in a sample of produced Phi mesons. Of course, she will have her hands full dealing with the relative efficiency with which her experiment can detect the slow kaons or the faster moving rho and pion, and other subtleties; but the measurement is not too difficult, and it will give her access to a verification of the inner workings of the strong interaction, and the probability of single gluon emission.

The right way to think, when we deal with the demise of a Phi meson or any other system that has multiple possible ways of kicking its legs, is an analogy I cooked up, and which I will dub the “picnic pie” analogy. Imagine you place your pie on the towel over some nice grass patch on a sunny Sunday afternoon; you are getting ready to attend to the pie, but then you are distracted by something and you leave it there. Now, assume that two different species of ants will come in at two different frequencies, which we can assume constant in time. Each ant will come, pick up a piece of the pie, and leave. In these circumstances, what fraction of the pie ends up in each of the two anthills? The answer is simply the ratio of the two frequencies.

The above might appear obvious, but a nuclear physicist could be confused by thinking at a system made of two different radioactive substances – say two different isotopes of Uranium, for instance. In that case the picnic pie analogy does not work: the faster-decaying isotope disappears much before the other, and the ratio of decays of one and the other is a function of time; what we have is two different pies, and one of them disappears quickly, the other remains for longer time. With elementary particles there is only one substance that can produce two or more different reactions, so the different decay rates affect the amount of one and the same substance, making the rule simpler – the fraction of decays into one or the other final state keeps constant, and it is the ratio of the two partial decay widths. Now, the latter is another concept that will have to wait for me to explain!

Comments