Several times a year I find myself exiting the Florida’s Turnpike at Yeehaw Junction and heading south. When I get to the small town of Okeechobee I take a left and head down Route 98 through Florida’s extensive agricultural backyard. Flanked by Lake Okeechobee on the west and the affluent cities of the Atlantic coast off to the east, the small towns nestled in this sliver of land support vibrant production of sweet corn, cattle, lettuce, and sugarcane. Cane-derived sugar ends up in many cupboards as table sugar, and also is found in many consumer products.

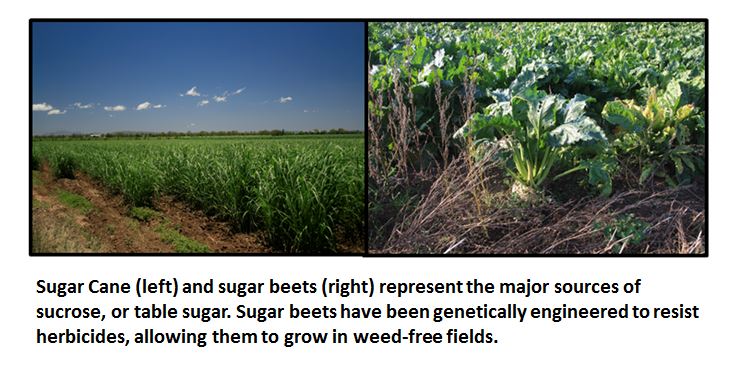

As reported on NPR, candy companies are caving in to consumer demands that the sugar they consume does not come from a GMO plant. To the scientist this is curious, because table sugar coming from sugarcane (which never was a GMO) is chemically identical to table sugar from GMO sources like sugar beets—it is sucrose. Sugarcane and sugar beets are partners in pleasure, together satisfying America’s sweet tooth. However, the demand for non-GMO sugar is exciting news only to the sugarcane industries, as their product has become increasingly more valuable with the no-GMO demand.

What is sugarcane? Sugarcane is a tropical grass, tall and lush. It grows meters high, forming tremendous oceans of green that wave and flow with the gentle breezes. It is a sight to behold. Usually my trips through sugarcane country happen in early morning, just as the sun kisses the sky, and the cane fields present a soft peaceful backdrop.

But environmentalists see these fields through a very different lens, and have targeted sugar cane production for decades. Their main objection is the burning of the cane, a counter intuitive practice for crop production. These massive fields are literally lit ablaze to produce the final crop. The fire removes the majority of leaves, leaving the sugar-laden canes behind for harvest. About 150,000 acres of sugar cane are burned each year, and environmental groups have vehemently opposed this practice. They claim that the practice generates greenhouse gasses, and puts thousands of tons of pollutants into the atmosphere that drift into the population dense cities of Florida’s east coast.

It seems like these environmental groups would welcome a low-impact alternative.

“Table sugar” is sucrose, a molecule containing a molecular fusion of fructose and glucose. Fructose and glucose are products of plant metabolism, and provide the basic building blocks of cellular structures. Plants manufacture glucose and fructose and then enzymatically link them to form sucrose. Sugarcane simply stores lots of sucrose.

Other plants also concentrate sucrose in storage organs. Fruits are a good example. Sugar beets have been bred to store massive amounts of sugar, approximately 20% of total weight, in a central root. They grow well in temperate climates and account for about half of sugar production.

One innovation made sugar beet production more attractive to farmers— glyphosate resistance generating “Roundup Ready” sugar beets. These plants are started from seed, and as they grow along with the field’s weeds for a few weeks. Then farmers spray an herbicide (glyphosate) over the top that kills the weeds and leaves the crop alive and well.

This works because the beets have been genetically engineered with an enzyme that resists the effects of the herbicide on disrupting plant physiology. The plants survive just fine, allowing them to grow without competition, and they eventually shade out emerging weeds. In many parts of sugar beet country a single application of glyphosate herbicide (usually about two soda cans per acre) does the trick. If weed pressures are heavy, they can go as high as 2.5 liters by law, but it is expensive and only used under extreme need. Plants are harvested months after application.

Sugar beet farmers find this technology amazingly helpful. One farmer I spoke with says that it saves him the tremendous costs of hiring crews for hand weeding, which runs about $500 per acre. Application of glyphosate—labor and other costs included, is $25 per acre. Hand labor is harder and harder to find, so this technology also allows growers to shift away from other herbicides which don’t share glyphosate’s minimal risk and low environmental impact.

“Glyphosate allowed us to streamline beet production,” said Suzanne Rutherford, a California sugar beet grower. “It is hard to find labor to weed many acres, so with Roundup Ready we don’t have do that anymore.”

It seems like the shift to GM sugar beets would be a positive move for farmers and the environment.

But over the last decade there has been a rise in anti-GMO hysteria. It has been fueled by misinformation from the internet, low-quality one-off scientific reports, and multi-billion dollar industries that thrive when conventional agriculture solutions can be cast as questionable or dangerous. Consumers are easy to scare, and the demands of a vocal minority have resonated with food producers, that now seek to source non-GMO ingredients for their products.

One great example is Hershey’s, a company synonymous with health food. As reported in the NPR piece, the Hershey Company is transitioning to all non-GMO ingredients, meaning using cane sugar over beet sugar. The empty calories of sugar-saturated candy now can be consumed without concern for what plant produced the sucrose. Again, sugarcane sugar (C12H22O11) is chemically identical to sugar beet sugar (C12H22O11).

The demand for non-GMO sugar has driven up the price of cane sugar and decreased the interest in GMO sugar beets. To cash in on that momentum, some sugar beet growers may soon gravitate to non-GMO varieties that require use of chemicals that lack glyphosate’s health and environmental safety profile, including cocktails of many herbicides that must be applied frequently and in perfect conditions. The alternative weed controls carry significantly more potential health risk to workers and potential environmental impacts.

In this blazing case of backwards thinking, consumers are demanding the worst choice for farmers and the environment. Technology was installed in GMO sugar beets to produce the same end product in a different time of year, in a different part of the country. They did so without voluminous black clouds of smoke, costly hand labor, or the use of old-school herbicides. This was an advance in science that enhanced worker safety and environmental stewardship from other practices.

It is another reminder that standing against genetic engineering is oftentimes standing against the best options for people and planet. The sugarcane and sugar beet each produce the same final product. It is truly troubling that companies are being coerced into costly decisions that have no effect on what the consumer eats, other than raising its cost, and producing it with greater environmental impact. It is what happens when we turn a blind eye to science, and accept marketing scams and activist campaigns over sound decisions made from evidence.

Comments