Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society

Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven SocietyNowadays researchers and scholars of all ages and specialization find themselves struggling with...

USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research

USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And ResearchThe 10th congress of the USERN organization was held on November 8-10 in Campinas, Brazil. Some...

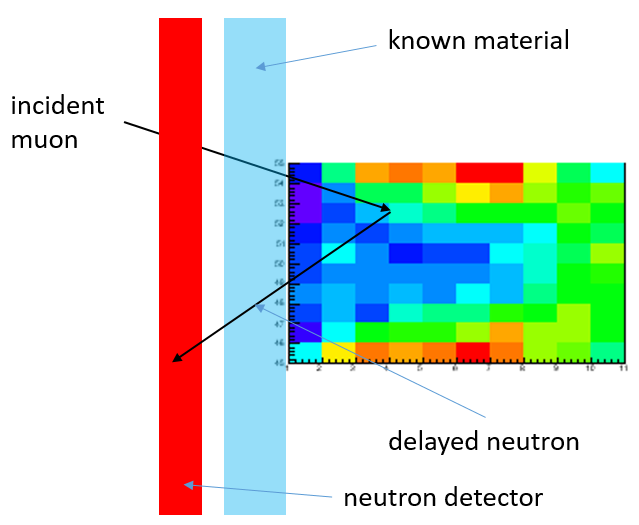

Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World

Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning WorldI am moving some baby steps in the direction of Reinforcement Learning (RL) these days. In machine...

Restoring The Value Of Truth

Restoring The Value Of TruthTruth is under attack. It has always been, of course, because truth has always been a mortal enemy...