Letter To A Demanding PhD Supervisor

Letter To A Demanding PhD SupervisorA fundamental component of my research work is the close collaboration with a large number of scientists...

Letter To A Future AGI

Letter To A Future AGII am writing this letter in the belief that the development of an artificial general intelligence...

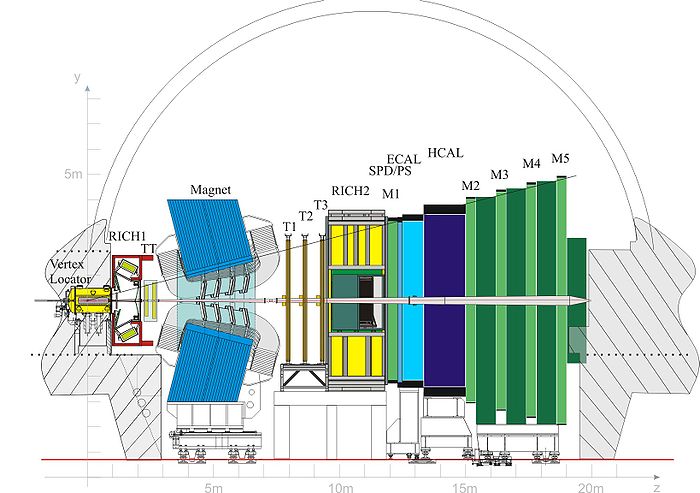

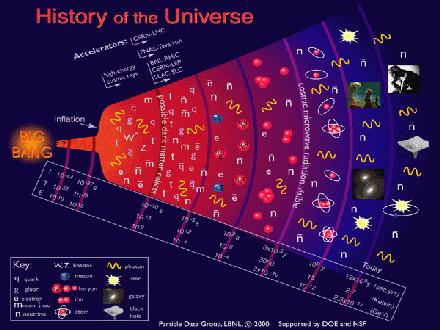

A Great Year For Experiment Design

A Great Year For Experiment DesignWhile 2025 will arguably not be remembered as a very positive year for humankind, for many reasons...

Living At The Polar Circle

Living At The Polar CircleSince 2022, when I got invited for a keynote talk at a Deep Learning school, I have been visiting...