Everyone has heard about bisphenol A (BPA). It’s primarily used as a raw material to make polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resins, both of which are high performance materials used in many consumer products that help to make our lives better and safer. But that’s probably not what you’ve heard.

What you may have heard is that we’re all exposed to BPA. And it’s true, we probably are all exposed to BPA. But unless you’re an exposure scientist who studies exposure to chemicals for a living, just knowing we’re exposed to BPA isn’t very useful without knowing a lot more.

In particular we need to know how much BPA we’re exposed to and whether those levels are safe or not. That concept is critical to understanding the safety of most anything we’re exposed to, whether intentionally or not. For example, taking one aspirin may safely eliminate your headache, but taking a whole bottle of aspirin may eliminate your life. The difference is important.

So just how much BPA are we exposed to and are those levels safe? This is where an important new study published in the journal Environmental Pollution provides some very useful information. What the researchers realized is that an enormous amount of data on consumer exposure to BPA is already available. It just wasn’t all in the same place where it could be most useful, until now.

It’s well known that people quickly eliminate BPA from the body through urine within hours of exposure. Measuring BPA in urine is considered the best way to evaluate exposure to BPA since what goes in (i.e., exposure) comes out in urine where it’s easy to measure.

What the researchers did was search the scientific literature for studies that measured levels of BPA in urine. They found more than just a few studies: “[i]n total, we obtained over 140 peer-reviewed publications, which contained over 85,000 data [points] for urinary BPA concentrations derived from 30 countries.”

The researchers then sorted the data by age group (adult men and non-pregnant women, pregnant women, and children) and country to assess whether exposure levels are safe or unsafe for these groups. That assessment was done by comparison of the exposure levels with safe intake limits set by government bodies worldwide.

Compared to what you may have heard, the results may surprise you: “[i]t is evident that the national and global estimated human BPA daily intakes in this study are two to three orders of magnitude lower than that of the TDI [Tolerable Daily Intake] … recommended by several countries.” In other words, actual exposure to BPA is hundreds to thousands times below the safe intake limit.

These results provide very strong support for the views of government bodies worldwide on the safety of BPA. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) answers the question “Is BPA safe?” with the unequivocal answer “Yes.”

What Did the Researchers Do and What Did They Find?

As noted by the researchers, “[t]o evaluate BPA’s potential risk to health, it is important to know human daily intake.” In general there are two ways to measure daily intake of a substance.

One way is to measure how much of the substance goes into the body. A second way is to measure how much of the substance comes out of the body as it is eliminated. The preferred approach for BPA, by far, is to measure how much BPA is eliminated from the body in urine, a technique known as urine biomonitoring.

The reason is that BPA is efficiently converted in the body to a biologically inactive metabolite after exposure, which is then quickly eliminated from the body in urine. Essentially the metabolite concentrates in urine, which makes it easy to measure with sensitive analytical instruments. As noted by a prominent group of researchers in regard to BPA and similar substances, “urine is the most dependable biomonitoring matrix for population research.”

This has not gone unnoticed by researchers who have generated urine biomonitoring data on BPA for more than 10 years. What the authors of this new study realized is that quite a bit of data has been generated over this time period, but it is difficult to comprehensively understand since the data is embedded in a wide variety of separate studies that were conducted for different purposes.

To resolve this dilemma, the authors searched the peer-reviewed scientific literature for urine biomonitoring data on BPA regardless of why the data was generated in the first place. By mining the literature in this way, the authors uncovered an astounding amount of data that, taken together, provides a deep understanding of human daily intake of BPA.

Overall, the authors found over 140 independent studies that reported urine biomonitoring data for BPA. Together the studies include more than 85,000 data points from individuals in 30 countries. The studies include a significant amount of data for pregnant women and children, which is important since these two groups are generally considered as subpopulations that might be more sensitive to effects from chemical exposures.

What Does The Data Mean?

The raw data that was analyzed simply measures the concentration of BPA, in the form of its metabolite, in urine. Without additional information, the raw data is difficult to understand or interpret with respect to safety.

To interpret the data, the researchers estimated daily intakes of BPA for comparison with safe intake limits established by government bodies worldwide. Intakes are fairly easy to estimate since studies on human volunteers show that BPA is entirely eliminated in urine after exposure. Essentially, what goes in (i.e., intake of BPA) is equal to what comes out (i.e., amount of the BPA metabolite in urine).

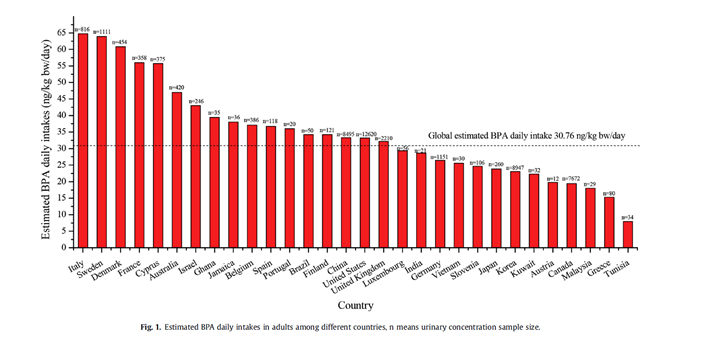

The results were presented in an easy to understand graphical format as bar charts that show estimated daily intakes of BPA by country for each of the three age groups. For example, estimated intakes for adults are shown in the bar chart below.

On a global basis, the estimated daily intake of BPA for adults is approximately 31 nanograms BPA/kilogram bodyweight. Estimated intakes on a country basis show only slight variation. With one exception on the low end, intakes for all other countries range from approximately 20-60 nanograms/kilogram bodyweight with each country differing from the global value by a factor of two or less.

This very low intake of BPA is consistent with how BPA is used and the low potential for people to contact BPA. Most BPA is chemically consumed as a raw material to make polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resins. Although we contact these materials in consumer products every day, the amount of residual BPA in these materials is very low, typically less than 50 parts per million.

The estimated daily intake for pregnant women is slightly higher at approximately 42 nanograms BPA/kilogram bodyweight and the estimated daily intake for children is approximately 60 nanograms BPA/kilogram bodyweight. Since other studies have shown that most BPA exposure comes from the diet, the relatively higher food intake for children may account for the higher BPA intake.

The authors also assessed whether their global daily intake estimates could be considered to be representative of the global population. Based on other recent research and their own analysis, the authors concluded that urine samples from a minimum of 1,000 people are required for an accurate estimate of daily intake for a population.

Considering the large amount of data available and analyzed in this study, the authors noted that “the estimated global BPA daily intakes in this study for adults, pregnant women and children were representative as the urine sample sizes were over 16,000 [for each group]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that reasonable worldwide human BPA daily intakes have been established for these population groups.”

Most importantly, the authors concluded by comparing the estimated daily intakes of BPA for each age group with the TDI (i.e., safe intake limit; 50 micrograms BPA/kilogram bodyweight) for BPA that has been established in several countries. In each case, as noted by the authors, it is apparent that estimated daily intakes are two to three orders of magnitude below the TDI. The TDI was established to be protective of all age groups, including pregnant women and children, so that conclusion is applicable to all age groups.

Since estimated daily intakes varied only slightly by country, that conclusion is also applicable to all countries. To go back to where we started, is anyone safe from BPA? Based on a large amount of data the simple answer is yes, we’re all safe from BPA.

Comments