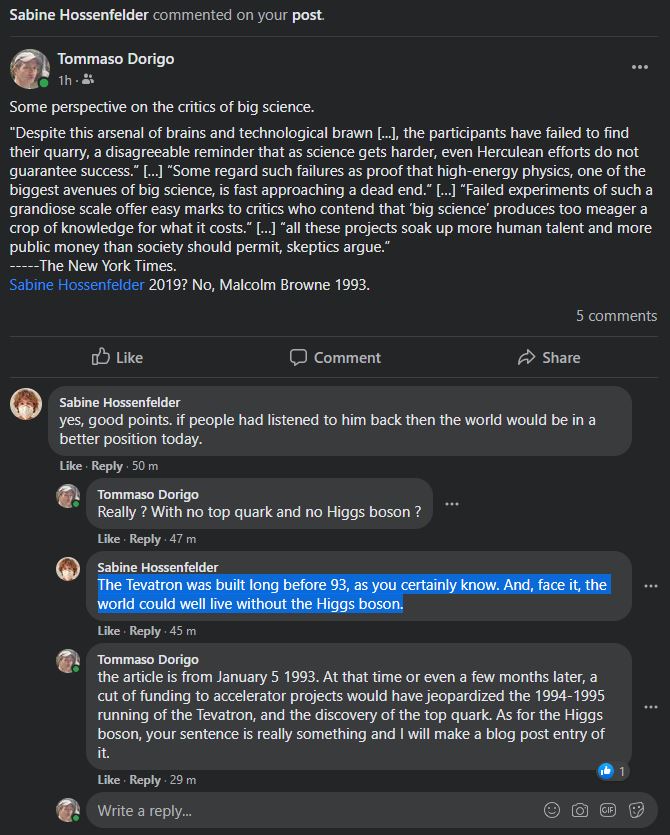

"Anti-scientific thinking" is a bad disease of our time, and one which may affect a wide range of human beings, from illiterate fanatics such as anti-vaxxers and religious fundamentalists on one side, to highly-educated and brilliant individuals on the other side. It is a sad realization to see how diversified and strong has become this general attitude of denying the usefulness of scientific progress and research, especially in a world where science is behind every good thing you use in your daily life, from the internet to your cell-phone, or from anti-cavity toothpaste to hadron therapy against tumours.

As every other aspect of human life, science communication has suffered a significant setback due to the ongoing Covid-19-induced pandemic. While regular meetings of scientific teams can be effectively held online, through zoom or skype, it is the big conferences that are suffering the biggest blow. And this is not good, for several reasons.

Muons are very special particles. They are charged particles that obey the same physical laws and interaction phenomenology of electrons, but their 207 times heavier mass (105 MeV, versus the half MeV of electrons) makes them behave in an entirely different fashion.

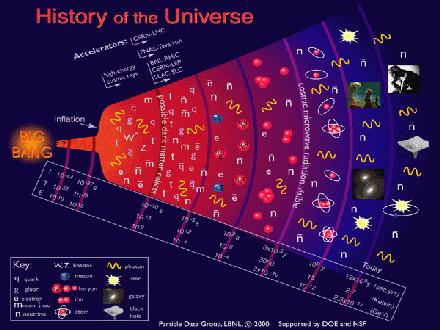

For one thing, muons are not stable. As they weigh more than electrons, they may transform the excess weight into energy, undergoing a disintegration (muon decay) which produces an electron and two neutrinos. And since everything that is not prohibited is compulsory in the subnuclear world, this process happens with a half time of 2 microseconds.

Have you ever behaved like an a**hole? Or did you ever have the impulse to do so? Did you ever use your position, your status, your authority to please yourself by crushing some ego? Please answer this in good faith to yourself - nobody is looking behind your shoulders. Take a breath. I know, it's hard to admit it. But we all have.

It is, after all, part of human nature. Humans are ready to make huge sacrifices to acquire a status or a position from which they can harass other human beings. Perhaps we have the unspoken urge to take revenge of the times when we were at the receiving end of such harassment. Or maybe we just tasted the sweet sensation it gives to use your power against somebody who can't fight back.

What is a twistor, and why should we care? Well, I may not be the most qualified blogger out here to give you an answer, but I will try to at least give you an idea. Before I do, though, maybe first of all I should say why I am discussing here a rather obscure mathematical concept, in this typically experimental-physics-oriented blog.

Twistor theory is a mathematical construction that dates back to the sixties, and is probably mostly known for some of its uses within string theory. Funnily enough, it has now been brought to the fore by Peter Woit, a mathematical physicist from Columbia University who became internationally renowned when he published his 2006 book "Not Even Wrong".

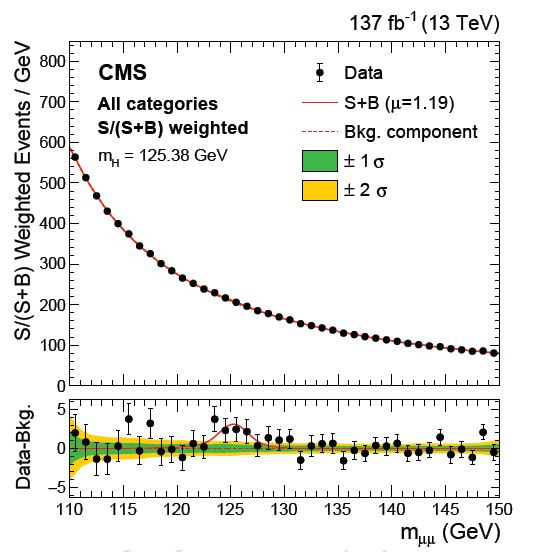

As of late we have been scratching the barrel of "straightforward" measurements of the properties of the Higgs boson, the particle discovered in 2012 by the Large Hadron Collider ATLAS and CMS experiments. But the one property determined in the measurement published yesterday by the CMS experiment was one that many of us were very interested to check.

If a particle is an elementary body, how many individual, distinct properties can it really have? For the word "elementary" means that it is intrinsically simple! But things are not so clear-cut in the subnuclear world. An elementary particle, while devoid of inner structure and dimensions, still has a number of measurable attributes. For the Higgs boson we may size up:

- mass (of course!)

Living At The Polar Circle

Living At The Polar Circle Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society

Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research

USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World

Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World