I have put this post under the "psychology" category, although it discusses a chess game, for one important reason. Chess is a game, an art, a sport - you can categorize it in many different ways. However, what characterizes chess the most, in my opinion (an educated one, as I am an amateur with a long past of chess tournaments) is the chance it gives to the players to mess up with each other's mind.

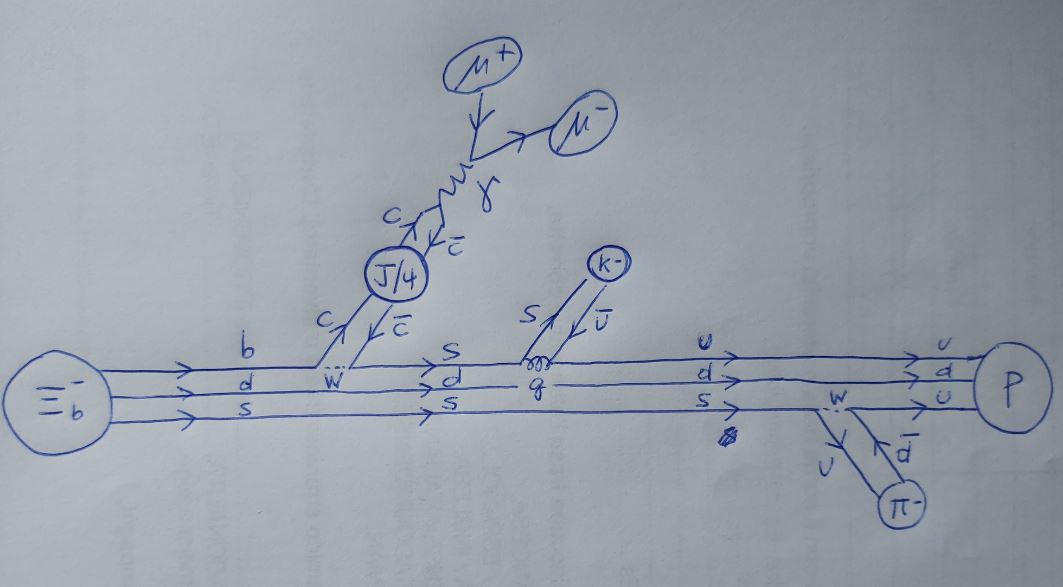

Wait, I can almost hear you say it: "Xi_b what? Let's move on, where's the sports section?" Ok, if you need to, please go. But do not underestimate excited Xi_b baryons. They are a helluva lot of fun to watch as they pop into existence and then decay in stages, as if stripping piece by piece, throwing out opaque layers of matter one by one, and finally exposing their naked beauty in full bloom.

Are you getting aroused yet? we are talking about a haDR-on here, don't be mistaken, but the matter is not less sexy than the stuff you'd get on the sports section anyway. For, you know, there is simply so much we still do not know about how quarks can create excited states of nuclear matter, that one cannot ignore any new development.

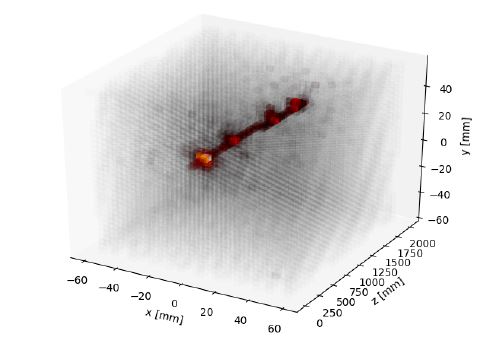

[This is the second part of a two-part article on Cosmic Messenger astrophysics. For part 1, please click here.]We can also "see" showers of secondary particles from cosmic rays thanks to the Cherenkov light they produce. Cherenkov light is emitted when charged particles travel in a medium at speeds higher than the speed of light itself! Light, in fact, slows down a little when it traverses a medium; energetic particles do not, so they create a conic "shock wave" similar to the boom of supersonic airplanes.

Today I wish to offer you, dear reader, the chance to contribute to scientific research in particle physics. And I claim you can do that by only leveraging basic high-school knowledge in mathematics and geometry. Let me explain what the problem is, first of all, and then I'll put you in the conditions of contributing!

Muons are subnuclear particles of high interest in collider physics. I could write about muons for ages, but it would not be of relevance for our problem of today, so let's just say they interact feebly with matter, so they traverse thick layers only depositing in them small amounts of energy (mainly in the form of electromagnetic radiation).

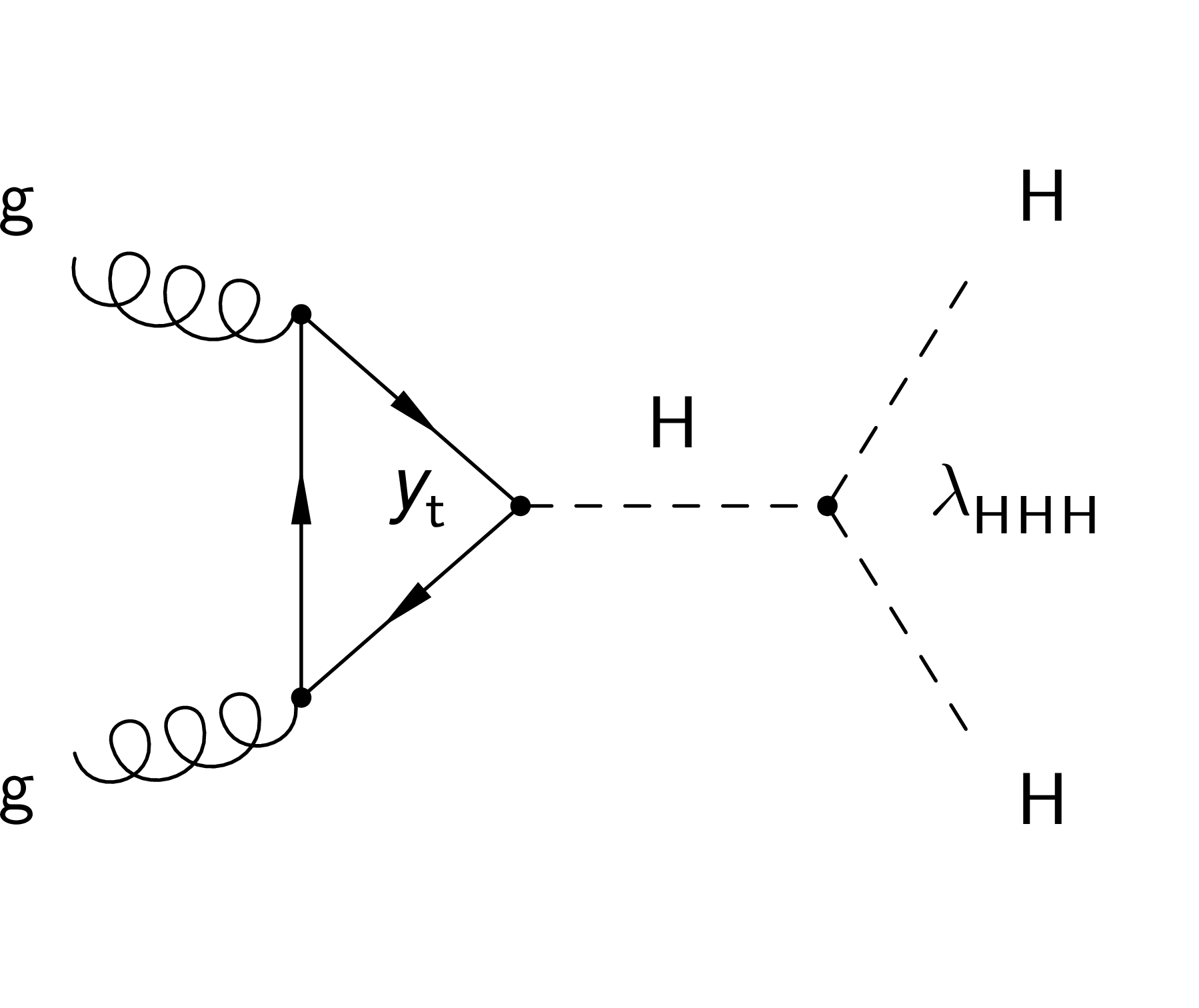

Eight years ago the CMS and ATLAS experiments, giant electronic eyes watching proton-proton collisions delivered in their interior by the CERN Large Hadron Collider (LHC), discovered the Higgs boson. That particle was the last piece of the subnuclear puzzle of elementary particles predicted by the so-called "Standard Model", a revered theory devised by Glashow, Salam and Weinberg in 1967 to describe electromagnetic, weak, and then strong interactions between matter bodies.

The Higgs boson itself is even older, having been hypothesized by a few theorists as far back as 1964 to explain an apparent paradox with massive vector bosons, particles that had to be massless in order to not violate a symmetry principle that could in no way be waived.

Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society

Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research

USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World

Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World Restoring The Value Of Truth

Restoring The Value Of Truth