In 1989 the CDF experiment was sitting on its first precious bounty of proton-antiproton collisions, delivered by the Tevatron collider at the unprecedented energy of 1.8 TeV. One of the first measurements that was produced was the measurement of the mass of the Z boson, which was at the time known with scarce precision by the analysis of a handful of candidates produced by the CERN SppS collider, at a third of the Tevatron energy.

No, this is not an article about top models. Rather, the subject of discussion are models that predict the existence of heavy partners of the top quark.

Inspired by my friend

Peter Woit's openness in discussing his work in progress (a thick textbook on the foundations of quantum mechanics), I feel compelled to come out here about my own project.

Just a quick link to allow you to browse a very nice set of pictures taken at CERN by Andri Pol. The subjects are physicists in their daily activities - brainstorming at the blackboard, cycling around the lab, bitching about the mess in the common coffee room, or working at various pieces of hardware:

you can

see them here. Enjoy!

Last Tuesday I was in Mantova, a pleasant little town in northern Italy, rich of monuments and treasures like the Palazzo Ducale, which hosts a vast collection of paintings and frescoes from reinassance artists. But I was not there for a private visit; I was in fact invited to comment and provide answers to questions that the audience of a movie, "The Hunt for the Higgs", were invited to ask after seeing it.

The host of the event was the "Cinema del Carbone", a small movie theater near the center of the town. The organizers called me there because they knew me from my previous participation to last years' Festivaletteratura, a literature festival which takes place yearly in September, where authors of books and other media get in touch with their public.

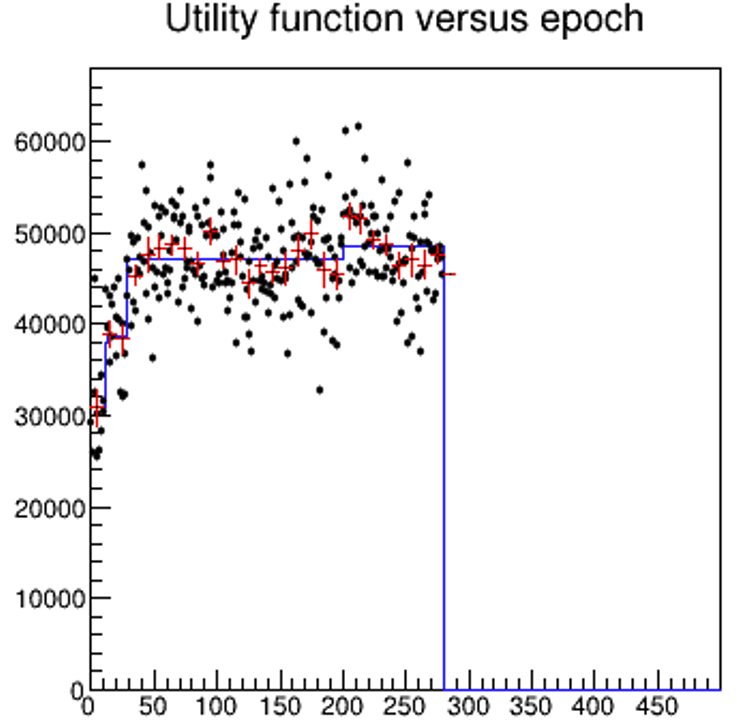

The Strange Case Of The Monotonous Running Average

The Strange Case Of The Monotonous Running Average Turning 60

Turning 60 On The Illusion Of Time And The Strange Economy Of Existence

On The Illusion Of Time And The Strange Economy Of Existence RIP - Hans Jensen

RIP - Hans Jensen