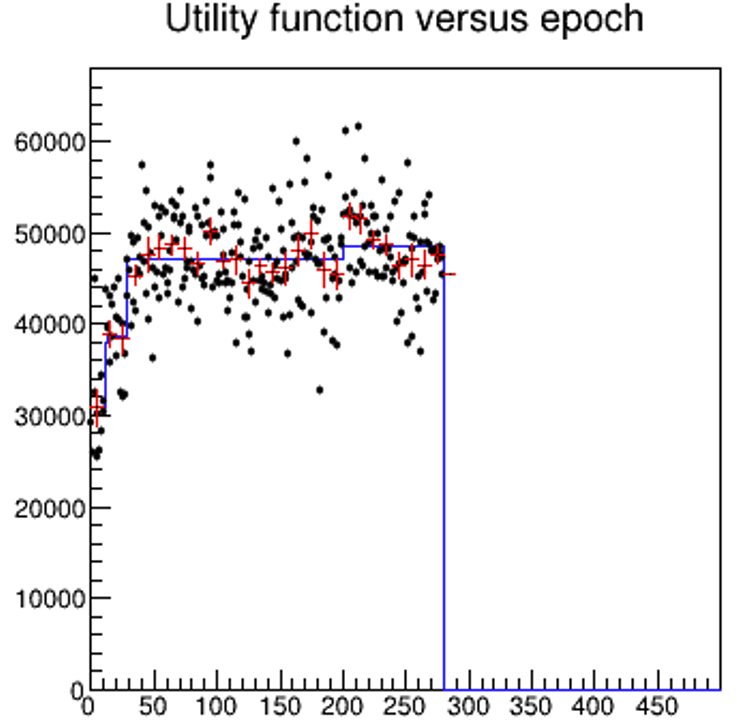

The Strange Case Of The Monotonous Running Average

The Strange Case Of The Monotonous Running AverageThese days I am putting the finishing touches on a hybrid algorithm that optimizes a system (a...

Turning 60

Turning 60Strange how time goes by. And strange I would say that, since I know time does not flow, it is...

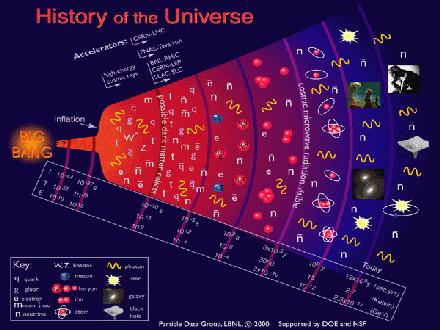

On The Illusion Of Time And The Strange Economy Of Existence

On The Illusion Of Time And The Strange Economy Of ExistenceI recently listened again to Richard Feynman explaining why the flowing of time is probably an...

RIP - Hans Jensen

RIP - Hans JensenToday I was saddened to hear of the passing of Hans Jensen, a physicist and former colleague in...